More than the usual transitions from one political party to the other, the arrival of the Trump administration requires critical strategic readjustments by education leaders who serve on the front lines. Among the extreme changes proposed by the administration are closing the U.S. Department of Education and sending federal education funds directly to the states.

Many of these attacks on 50 years of education policy—from civil rights enforcement in schools to evidence-based research grants to universities to teacher professional development to teaching about systemic racism and human sexuality—are already underway though significant funding cuts or policy changes. The moment to take action is now.

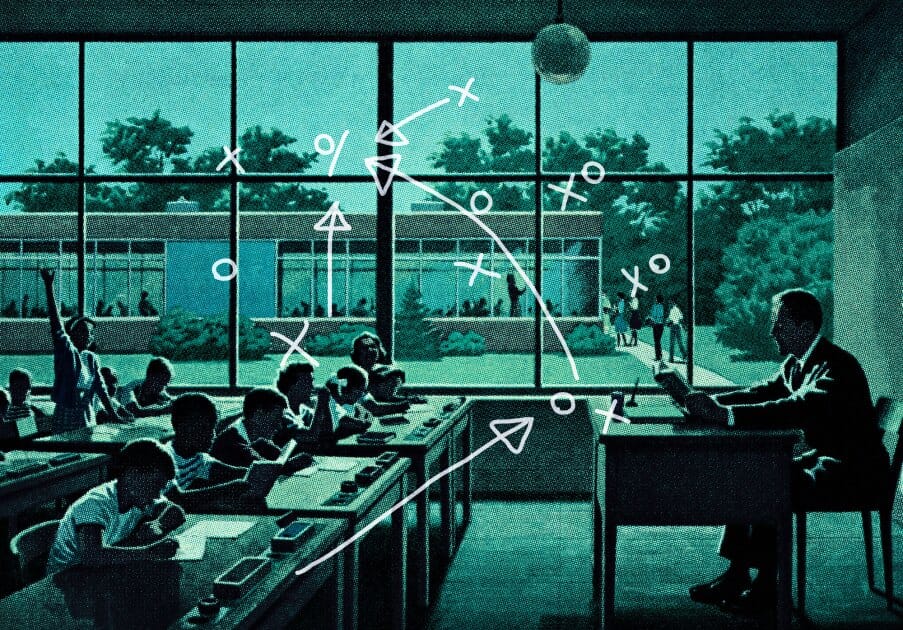

However, education leaders will not be successful in battles with the Trump administration if we use the same tired political playbook. One only needs to observe how the Republican-led U.S. House of Representatives recently took down multiple university presidents to realize that a new strategic playbook is necessary for the battles ahead.

Wars and pandemic are crises that demand immediate action. The same can be said for a presidential administration with no regard for the current public American education system. Here are some nontraditional offensive and defensive strategies for school principals, superintendents, chief state school officers, and other educators to consider in this new K-12 policy landscape.

One tactic for surviving the Trump years is to shift from battling for more funds to developing new partnerships with outside organizations. The focus should be on alternative sources of social, political, and financial support for the schools through cross-sectoral partnerships with organizations such as corporations, hospitals, and universities. Moreover, focusing on external partnerships with noneducation groups will give educational leaders new political capital when they want to challenge the Trump administration.

In these new partnerships, science-oriented corporations, for example, could provide mentors for budding scientists. Businesses with vacant office space could rent that space for high school classrooms. Suburban public school systems could cut their bus fleets in half by partnering with public transit systems to transport high schoolers.

Education leaders who engage in these types of collaborations could save school systems millions of dollars in operating and capital expenses, while also exposing students to private-sector jobs. Forty years ago, I worked in a partnership of social service agencies, businesses, the state government, and the University of New Hampshire in a cooperative effort to build the first public transit system in southeastern New Hampshire. This outside-the-box collaboration was successful because numerous organizations, both public and private, education and other sectors, contributed new ideas and new political capital.

We know that students in schools with health-care partnerships can do better academically, so schools would also benefit from accelerating partnerships with school-based health centers and teaching hospitals. Additionally, those partnerships can create more pipelines for low-income and underserved students into the health-care professions.

We should also strive for every American school system to have a meaningful relationship with a local institution of higher education. University partnerships can help low-income children find pathways to a college education while also developing more research based on community-oriented concepts for improving teaching and learning.

Johns Hopkins University, for example, provides Baltimore schoolchildren with eye care and science, technology, engineering, and math activities, as well as many undergraduate-student volunteer tutors.

Funding these partnerships may well become more difficult in the Trump years. The new administration has already revoked hundreds of millions of dollars in federal contracts for education research, and closing the Education Department would imperil even more funding. However, I hope and expect universities that are already home to education research centers to find new funding avenues even during the Trump years, perhaps by securing funding from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services if not the Education Department.

In my experience, school systems often let their bureaucracy get in the way of successful K-12-university partnerships. Partnerships should be transparent and collaborative with resources and responsibilities shared equally for maximum success.

A second defensive strategy for educators is to claim a seat at the table when federal education responsibilities are redistributed. Currently, only about 10 percent of public school funding (except for special education) is federal, and states are already the main implementer of federal education programs. Therefore, it should not be a big leap for state and local education leaders to find strategic ways to support the administration’s preference for more state, local, and family control of education policy and resources.

If, for example, the Trump administration continues to push for more voucher funds, K-12 leaders should join the conversation and work to make sure the vouchers go to those most in need.

A third and final suggestion for strategic realignment is to create a united front for K-12 innovation. During the crisis of World War II, the British government formed a war cabinet that included leaders from the Liberal, Conservative, and Labour parties. In American education’s current crisis, leaders should emulate the warfare strategy by adopting a temporary truce between traditional, charter, public, private, and home school. In this critical period for education policy, it would be a strategic mistake and a waste of resources if advocates for these K-12 schooling approaches continue to oppose each other in the upcoming policy debates.

Sometimes, political warfare requires strange bedfellows. In these times, all K-12 advocates, whatever their primary cause, should be allies in advocating public- and private-sector support, through cross-sectoral partnerships, for the transformation of American education.

Education leaders should recognize that changing political strategies or embracing new political allies cannot blunt the entirety of the Trump administration’s plans for American education.

Closing the federal Education Department would end its enforcement of civil rights in schools and colleges, a loss that would hit underserved students, female athletes, and LGTBQ+ students the hardest. It would also cause more chaos in the student financial-aid programs.

I hope that educational leaders will not need to manage every challenge threatened by the Trump administration. But in case we do, let’s develop a courageous political strategy around which we can all unify. Our students, parents, and teachers deserve nothing less.

2025-02-27 17:00:00

Source link