Will immigration agents carry out arrests and raids at schools?

It’s a question on the minds of educators in districts and schools with large numbers of immigrant students as President-elect Donald Trump prepares to take office next month with a pledge to carry out mass deportations.

And it’s a question that grew more urgent Wednesday following a news report that Trump plans to rescind a longstanding policy that has discouraged immigration agents from carrying out enforcement activities in places considered to be “protected areas”—schools; hospitals; churches; and other places where children gather, such as bus stops, after-school programs, and child care facilities.

NBC News reported that Trump plans to rescind the policy as soon as his first day in office. The news organization cited three anonymous sources with knowledge of the plan.

The development comes as the man Trump has tapped to become his border czar, Tom Homan, has started to outline what the mass deportation operation might look like, indicating that it would first focus on undocumented immigrants who pose a public safety threat. But it’s unknown how extensive the operation could grow, and how many U.S. students could be affected in some way.

An estimated 5.5 million children lived with an unauthorized immigrant parent in 2019, representing about 7 percent of the U.S. child population, according to the Migration Policy Institute think tank. Of these children, 4.7 million, or 86 percent, were U.S. citizens; 726,000, or 13 percent, were themselves unauthorized.

For more than a decade—including throughout Trump’s first administration—schools and other places where children gather, including bus stops, after-school programs, and child care centers, have been considered “protected areas” or “sensitive locations” where immigration agents generally can’t carry out arrests and raids without approval from agency headquarters.

“To the fullest extent possible, we should not take an enforcement action in or near a location that would restrain people’s access to essential services or engagement in essential activities,” Homeland Security Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas wrote in 2021 in the latest version of the memo outlining this policy. “This principle is fundamental. We can accomplish our enforcement mission without denying or limiting individuals’ access to needed medical care, children access to their schools, the displaced access to food and shelter, people of faith access to their places of worship, and more. Adherence to this principle is one bedrock of our stature as public servants.”

Educators and others who work with immigrants had lately been pointing to the 2021 memo in an attempt to assuage families’ fears of the possibility of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement officers showing up at schools.

But Project 2025—the Heritage Foundation-led, conservative policy agenda developed by a number of Trump allies and former Trump administration officials—called for rescinding such policies. And now it appears that might be one of the first immigration-related moves of Trump’s second term—one that’s fully within his purview as an executive branch policy.

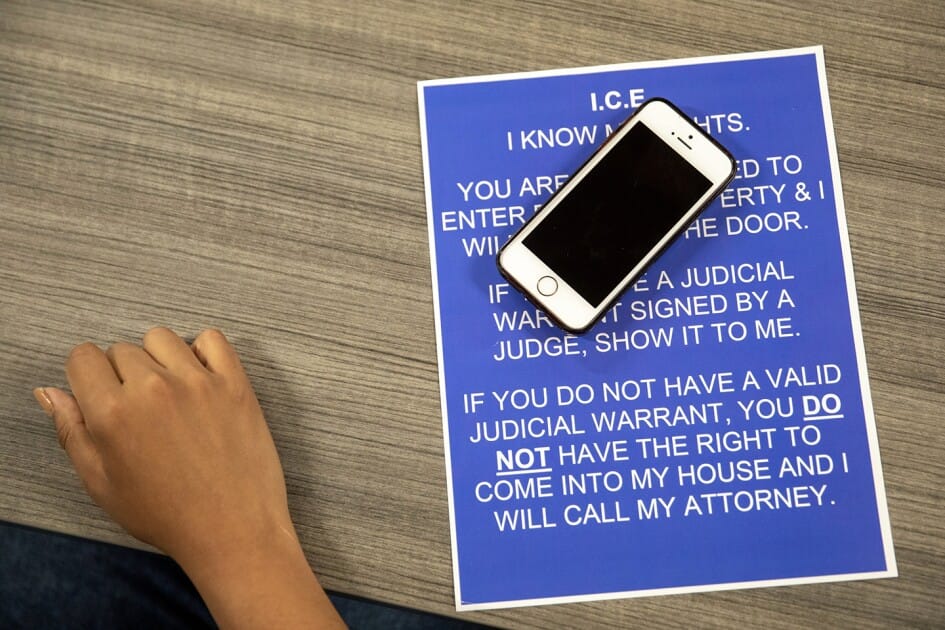

Absent that memo, some additional legal protections make schools unique areas with some protection from immigration enforcement. But significant uncertainty remains. It’s why experts and educators alike say schools should proactively remind staff about school policies on interacting with ICE officials and remind families of their rights—even as leaders aren’t sure of what’s to come.

The school committee for the Chelsea school district, north of Boston, passed a safe haven resolution in 2017 directing schools not to communicate with immigration officers and to protect student information from federal agents—only releasing it with parents’ permission or when a judicial warrant or court order compels it.

Following the presidential election, and in response to families’ concerns about stepped-up immigration enforcement, the Chelsea school committee is revisiting the resolution for any possible updates, said Superintendent Almi G. Abeyta. Uncertainty about the future of federal immigration policy complicates this work and Abeyta’s ability as superintendent to calm families’ fears.

“What I’ve been saying is, ‘we don’t know, let’s wait to see what happens, and we can go from there,’” she said. “We’re waiting, but we’re trying to gear up and educate our families and our communities [about their rights] as well.”

A longstanding legal precedent should prevent immigration enforcement at schools, a legal advocate says

Unlike with other locations considered protected areas, immigration enforcement at schools poses a clear constitutional problem, said Thomas A. Saenz, president and general counsel of the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund, or MALDEF.

That’s because of the 1982 U.S. Supreme Court decision in Plyler v. Doe, which made access to a free, public education a constitutional right regardless of a student’s immigration status.

“It would, in our view, be a constitutional violation to engage in immigration enforcement activity at a school. Why? Because doing so would deny the constitutional right to attend school regardless of status,” Saenz said.

Lawyers with MALDEF represented the plaintiffs in the 1982 case—four families that challenged a Texas school district’s policy of charging tuition to families that didn’t provide proof of legal immigration status for their children.

Saenz believes the Plyler decision will remain in place for the foreseeable future both because previous efforts to undermine it have failed and because the decision was incorporated into federal law in 1996.

Still, the Heritage Foundation earlier this year outlined a strategy to bring Plyler v. Doe back before the Supreme Court, which today has a 6-3 conservative majority and might be more amenable to overturning it. The think tank recommended that states require school districts to record their students’ immigration status and charge tuition for students from undocumented families—actions that would directly go against Plyler and likely prompt legal challenges.

However, what precisely will happen in the near future remains uncertain. So Greg Chen, senior director for government relations at the American Immigration Lawyers Association, and others advise schools and families to be careful with sensitive information about students and to stay alert.

“We are entering into a dramatically different era here with the beginning of the second Trump administration, where they have made it crystal clear that they are going to enforce the law and even go beyond the law, likely in many situations,” Chen said.

Chen also noted that federal policy governing how immigration agents do their jobs does not apply to local law enforcement, which includes school resource officers. In many places, local police have written agreements with ICE outlining how they’ll cooperate with federal immigration agents. Other local governments have policies stating that local police won’t cooperate with immigration authorities.

The National Association of School Resource Officers has not yet shared with school resource officers “any information … regarding possible changes in immigration policy, nor has it communicated any reminders about existing DHS policy around sensitive/protected locations including schools,” the group said in a statement to Education Week.

State and local leaders reinforce policies protecting immigrant students

Some districts and at least one state, however, are proactively outlining for school staff how they should handle requests from immigration officers.

What I’ve been saying is, ‘we don’t know, let’s wait to see what happens, and we can go from there.’ We’re waiting, but we’re trying to gear up and educate our families and our communities [about their rights] as well.

Almi Abeyta, superintendent, Chelsea, Mass.

On Dec. 4, California Attorney General Rob Bonta released an updated guide for schools on how staff should handle requests from immigration officials—for example, schools aren’t compelled to provide ICE agents with access to student records if they only have an administrative warrant as opposed to a warrant signed by a judge, according to the guide. In addition, the guide reminds schools of their obligations under federal law not to release private student information without their parents’ consent.

In addition to serving as a reminder of state and federal laws and policies, the guide includes model policies school districts could adopt.

The mass deportation promises from the incoming Trump administration, as well as the possibility that the “protected areas” policy could be rescinded, prompted the reminder, according to Bonta’s office.

“Because of this, and because exceptions to the policy exist, local educational agencies should have plans in place in the event that a law-enforcement officer requests information or access to a school site or a student for immigration-enforcement purposes,” the updated guide reads.

Since 2018, California’s Assembly Bill 699 has prohibited school officials and district employees from collecting information or documents addressing the citizenship or immigration status of students or family members. It also requires school districts to adopt policies limiting assistance with immigration enforcement.

ImmSchools, a Texas nonprofit that partners with schools in multiple states to create welcoming environments for immigrant students and families, encourages individual districts to establish their own policies addressing what to do regarding immigration enforcement.

The organization partners with school districts in multiple states to offer training for educators so they better understand immigration laws and policies. Among the group’s main recommendations is that schools direct families to information about their rights, including federal privacy protections for student information including the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act, or FERPA, said Viridiana Carrizales, ImmSchools’ founder and CEO.

“We need to make sure that our families know what their rights are, so that they know when those rights are being violated,” Carrizales said.

In Chicago, Los Angeles, and New York City, school districts have issued advice to building administrators, such as directing school staff to consult with district lawyers before engaging with ICE requests.

In 2020, then-school board member Falio Leyba-Martinez championed a safe zone resolution for the Camden district in New Jersey emphasizing that schools are safe spaces for immigrant students and families and that district employees would only help immigration officers if they were legally required to do so.

Now a Camden city councilman, Leyba-Martinez recognizes the resolution cannot guarantee a student’s protection from immigration enforcement. But it adds a layer of extra security and reassurance in the district to put families at ease.

Leyba-Martinez acknowledges that not all school boards would embrace a similar resolution. But he argues that school board members should recognize that if they serve immigrant families, regardless of their status, such safe zone policies send an important message that their local community values them.

“I would tell people that want to get this done to put up the fight as big as it is,” he said. “They’re elected onto the school board to represent all of the students, no matter what their status is in this country.”

2024-12-11 21:49:27

Source link