At least eight states are trying to crack down on attempts to remove books in school libraries, passing legislation that gives librarians more leeway in selecting materials, sets up formal processes for responding to challenges, and bars schools from pulling books from the shelves for ideological reasons.

Dubbed “freedom to read” laws by supporters, this legislation has emerged over the last two years, a response to the growing number of challenges to books for content related to race and LGBTQ+ issues in the post-pandemic period.

The policies—passed in California, Delaware, Illinois, Maryland, Minnesota, New Jersey, Rhode Island, and Washington—vary by jurisdiction, but most state that books can’t be excluded from a public school library solely because of the background or views of the author. Nor can books be removed due to “partisan, ideological, or religious disapproval.” The laws also require schools to create and enforce a policy for responding to challenges from teachers, parents, or students that includes the input of library staff and school and district leadership.

Still, most of this legislation hasn’t been tested, and it’s unclear yet what effect they will have on the broader political landscape now shaping the content of school libraries, experts say.

“These laws may have a meaningful short-term effect by raising the bar for book removal and discouraging challenges that rest primarily on identity-based objections,” Katie Spoon, a data science fellow at Stanford University, said in an email. Spoon has published research on the effect of book challenges in recent years.

But long-term “freedom to read” laws could potentially have an opposite effect, she said.

“In more conservative areas, especially those with fewer challenges on record, children’s books featuring diverse characters may simply not be stocked in school libraries to begin with.”

New laws could change how and where book bans happen

The two main organizations that track challenges to books in school libraries—the American Library Association and PEN America—have both reported increases in book banning attempts since 2020.

In part, the uptick can be traced to new state laws dictating what content schools can teach and giving parents and community members the authority to challenge materials.

Since 2021, at least 20 states have passed legislation restricting what students can be taught about race or gender. Some states, most notably Florida, have also granted parents more decisionmaking power over school library collections. PEN America has found that some book bans are direct consequences of these laws.

New “freedom to read” laws are designed to maintain access to books for students, something that should be a “slam-dunk American value,” said Sam Helmick, the president of ALA.

The legislation would also ensure that districts follow a standard procedure in reviewing books that have been challenged, Helmick said. For instance, some of the laws require that the challenged book stay on the shelves while the review process is underway, rather than being pulled immediately.

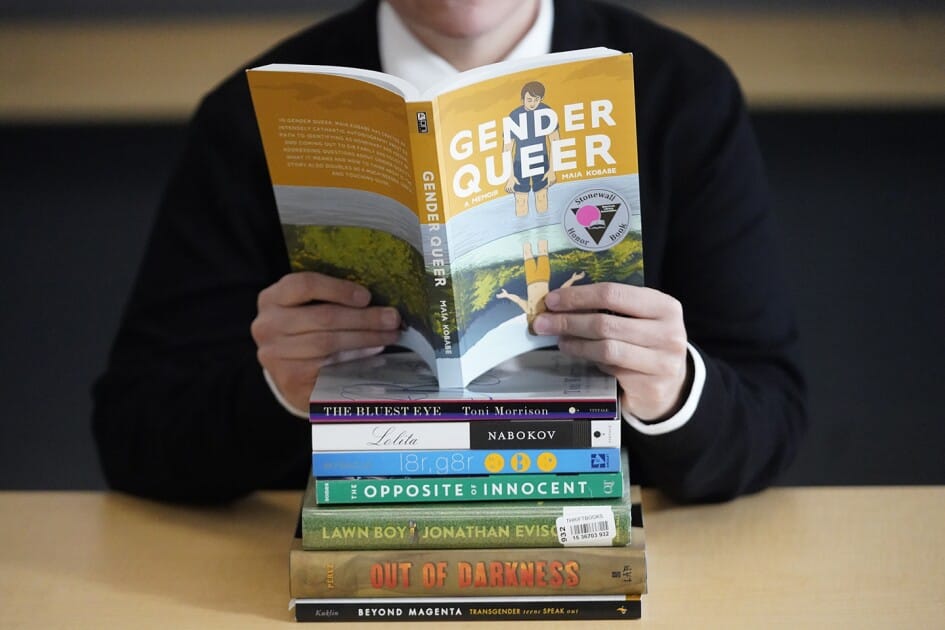

In the 2023-24 school year, PEN America found that more than 10,000 books had been removed at least temporarily from public schools. The organization drew from public records and media reports.

The ALA counted differently, tallying reports submitted to them directly from library professionals and attempts that have made national news. The group counted 821 attempts to censor library materials in calendar year 2024, spanning 2,452 individual titles.

Florida leads the nation in book challenges, according to PEN America data, followed by Texas and Tennessee. The list of states that have passed “freedom to read” laws doesn’t overlap much with the list of those with the most attempted challenges. Blue states have passed these laws, while red states tend to see the most challenges.

But this doesn’t mean the laws couldn’t have an effect, as state-level data obscures more local trends, said Spoon.

“We found that bans were most often in counties that lean Republican but are becoming more politically competitive (i.e., less Republican) over time, suggesting that local political dynamics matter more than broad red–blue state-level distinctions,” she wrote.

At least one blue state, New York, failed to pass a proposed bill. In December, Gov. Kathy Hochul, a Democrat, vetoed a proposal that would have required schools ensure librarians are “empowered to curate and develop collections that provide students with access to the widest array of developmentally appropriate materials available.”

In a Dec. 19 memo on the legislation, Hochul noted that the state education department had already provided guidance on school library collection curation. “I am concerned that the unclear wording of this bill will do more to confuse than to clarify schools’ obligations and school librarians’ roles,” she wrote.

Those opposing the laws cite parents’ rights

While the ALA and PEN America have voiced support for these laws, some in the “parents’ rights” movement argue that the laws strip students’ families and other adults in the school community of their prerogative to make decisions about what counts as appropriate reading material for children.

“It’s their responsibility,” said Jonathan Butcher, the acting director of the Center for Education Policy at the Heritage Foundation, a conservative group that has advocated against diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives in schools.

“It is financially impossible to carry every book in a school library,” he said. “They have no choice but to be particular about the books that are included on school library shelves.”

The criteria that some “freedom to read” laws decree can’t be grounds for removal—the authors’ views, or an individual’s ideological disapproval—are “exactly the reasons” that parents and educators should be considering when determining whether a book should remain on the shelves, he said.

Butcher also takes issue with the idea that removing a title from a school library constitutes banning the book, saying that students are still free to check the text out from a public library or buy a copy.

That’s the same argument that a federal appeals court made in May of last year, deciding that a Texas library’s decision to remove books couldn’t be challenged under the First Amendment based on patrons’ right to receive information.

But Helmick, with the ALA, said Butcher’s justification doesn’t reckon with how school libraries actually work in practice. For many students who don’t have public libraries nearby or the financial ability to buy new books regularly, Helmick said, the school library may be their only option.

2026-01-07 21:57:46

Source link